Fantasy and free play

The power of being provoked and the victory of writing outside recognized structures

Here are nine things I’ve recently read, watched and attended, and heartily enjoyed!

1. Free Play by Stephen Nachmanovitch

This book is exceptional. It is the best thing I have ever read on playing and creating. It’s not even specifically about writing – the author is a musician – but it is both magical and utterly grounded – and it’s already having an effect on my writing practice.

The book’s purpose, Nachmanovitch says, is ‘to propagate the understanding, joy, responsibility, and peace that come from the full use of the human imagination’.

I have copied out dozens and dozens of excerpts – too many to mention here – but here are six favourites (a lot, I know, but it’s SO good):

In dealing with unconscious mind, we’re dealing with an ocean full of rich, invisible life forms swimming underneath the surface. In creative work we’re trying to catch one of these fish; but we can’t kill the fish, we have to catch it in a way that brings it to life. In a sense we bring it amphibiously to the surface so it can walk around visibly; and people will recognize something familiar because they’ve got their own fish, who are cousins to your fish.

Does the poem exist before it is written? Does the idea exist before it is known? Definitely!

The child’s instinctual desires to do, to be the cause, to explore, to arrange things, evolve into deeper passions later in life. Such are the ripened passions of someone who has already experienced some suffering, fought through some of the obscurations and disappointments, and come back to the art form, to a renewal of creativity. Then the drive to create is not just the entrancing magic of the child’s fascination; there is the erotic fascination, involving both love and tension, the complex dance of push and pull. It is like the complex dance of coming back to an old love.

The idea of work to be done is for me so closely bound up with the idea of the arranging of materials and of the pleasure that the actual doing of the work affords us that, should the impossible happen and my work suddenly be given to me in a perfectly completed form, I should be embarrassed and nonplussed by it, as by a hoax.

Stravinsky, The Poetics of Music

The workmanlike attitude is inherently nondualistic – we are one with our work. If I act out of a separation of subject and object – I, the subject, working on it, the object – then my work is something other than myself; I will want to finish it quickly and get on with my life.

…But if art and life are one, we feel free to work through each sentence, each note, each colour, as though we had infinite amounts of time and energy. Having this lavish, abundant disposition toward our time and our identity, we can persevere with a steady and cheerful confidence, and thus accomplish infinitely more and better.

The raw material is a kind of flow – Herakleitos’ river of time, or the great Tao, flowing through us, as us. Mysteriously flowing through, unstoppable and unstartable. At its source, it does not appear or disappear, does not increase or decrease, is neither tainted nor pure. We can choose to tap into it or not to tap into it; we can find ourselves unwillingly opened up to it or unwillingly cut off from it. But it’s always there.

I enjoyed this podcast interview with the author here too. Incidentally, his PhD supervisor and lifetime mentor was the anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who, among many other accomplishments, conceived the theory of the double-bind, which the psychiatrist RD Laing, among others, went on to write much about.

2. Fantasy at the British Library – on until 25 February

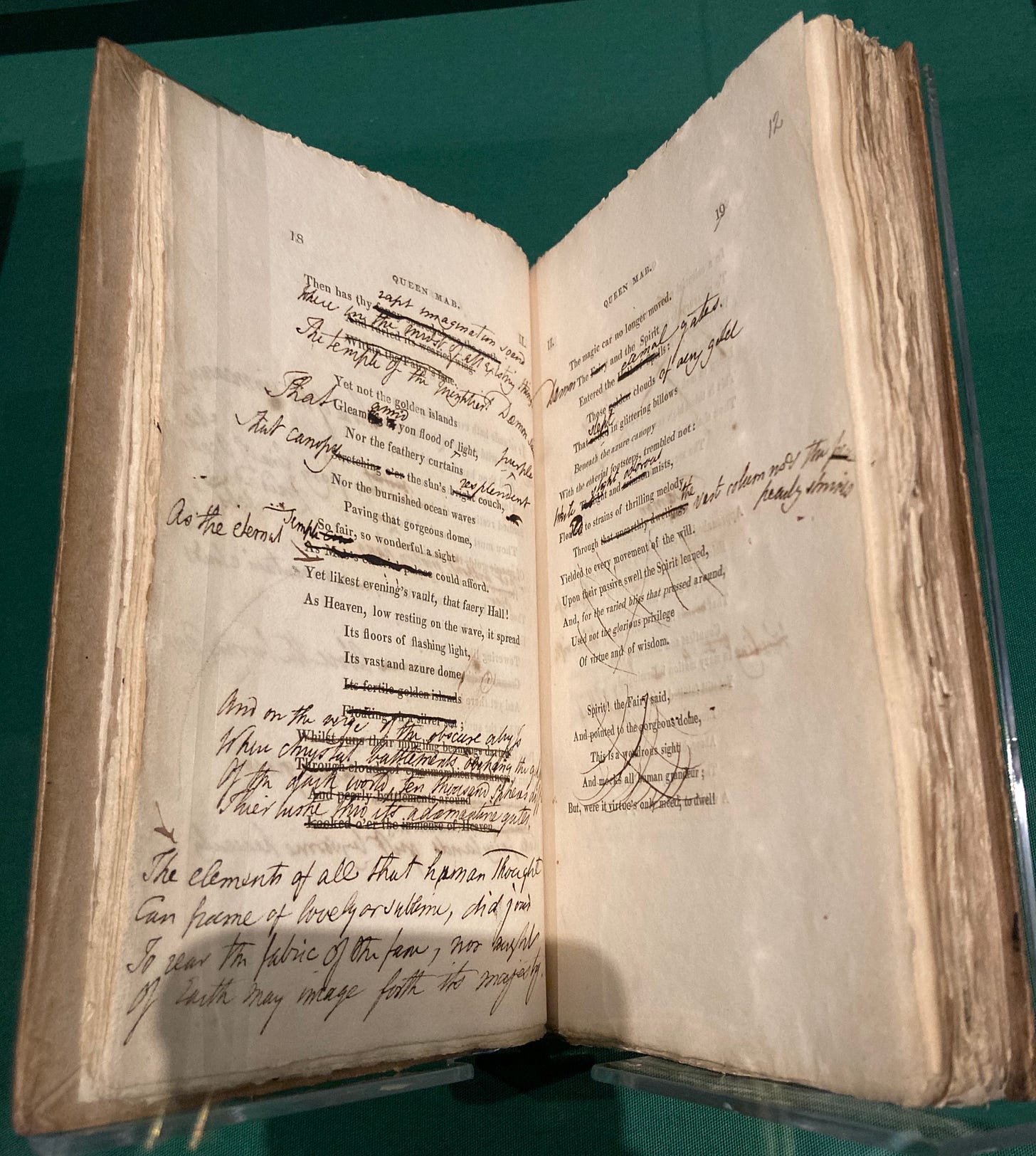

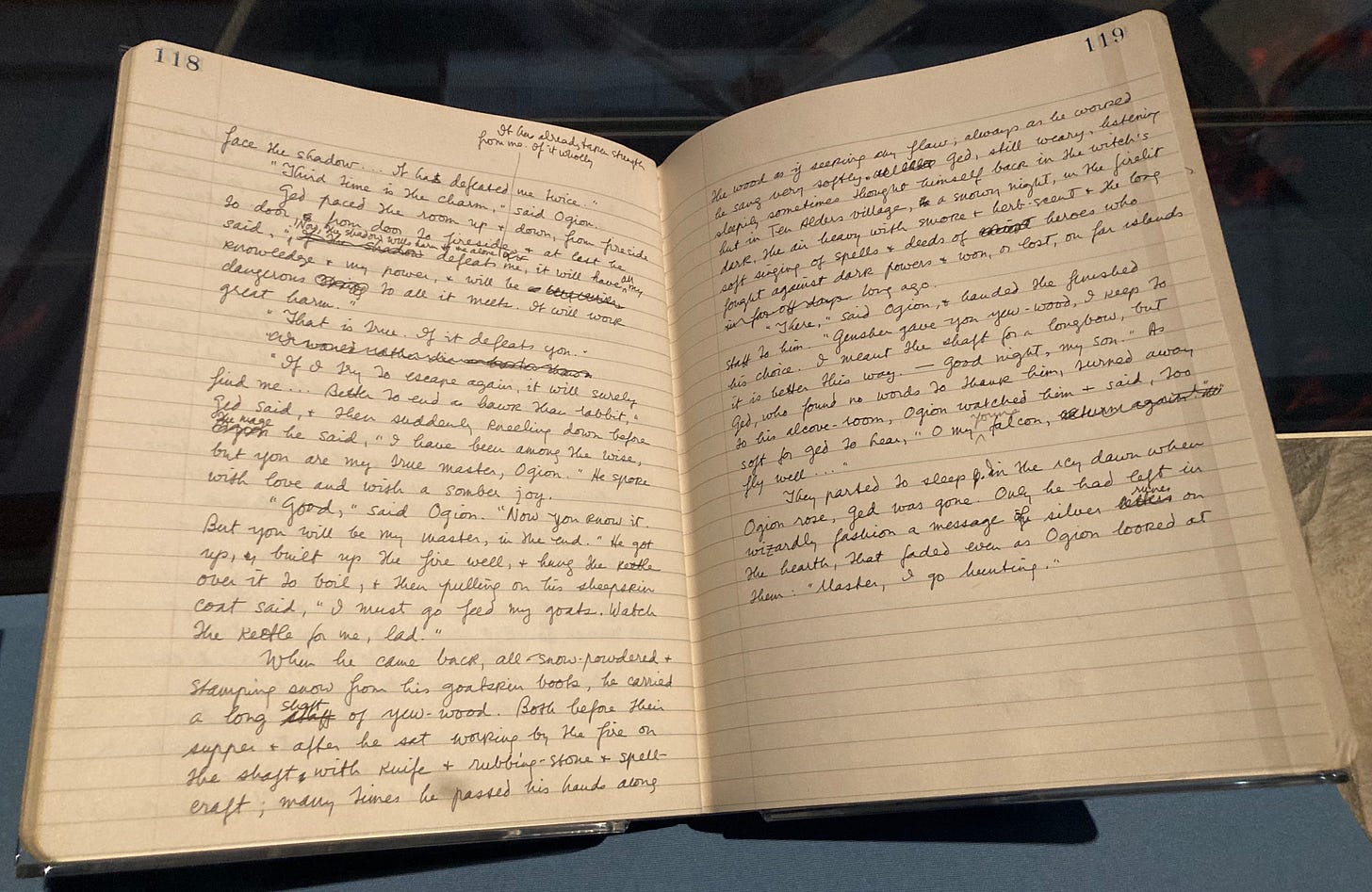

This is an extraordinary exhibition at the British Library on fantasy in literature. I don’t even read fantasy and I was blown away. It contains many, many original manuscripts. Guardian review here.

Seeing Shelley’s handwritten changes to the first edition of Queen Mab (1813) was one of the most exhilarating things I have ever seen:

Other handwritten manuscripts include Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea:

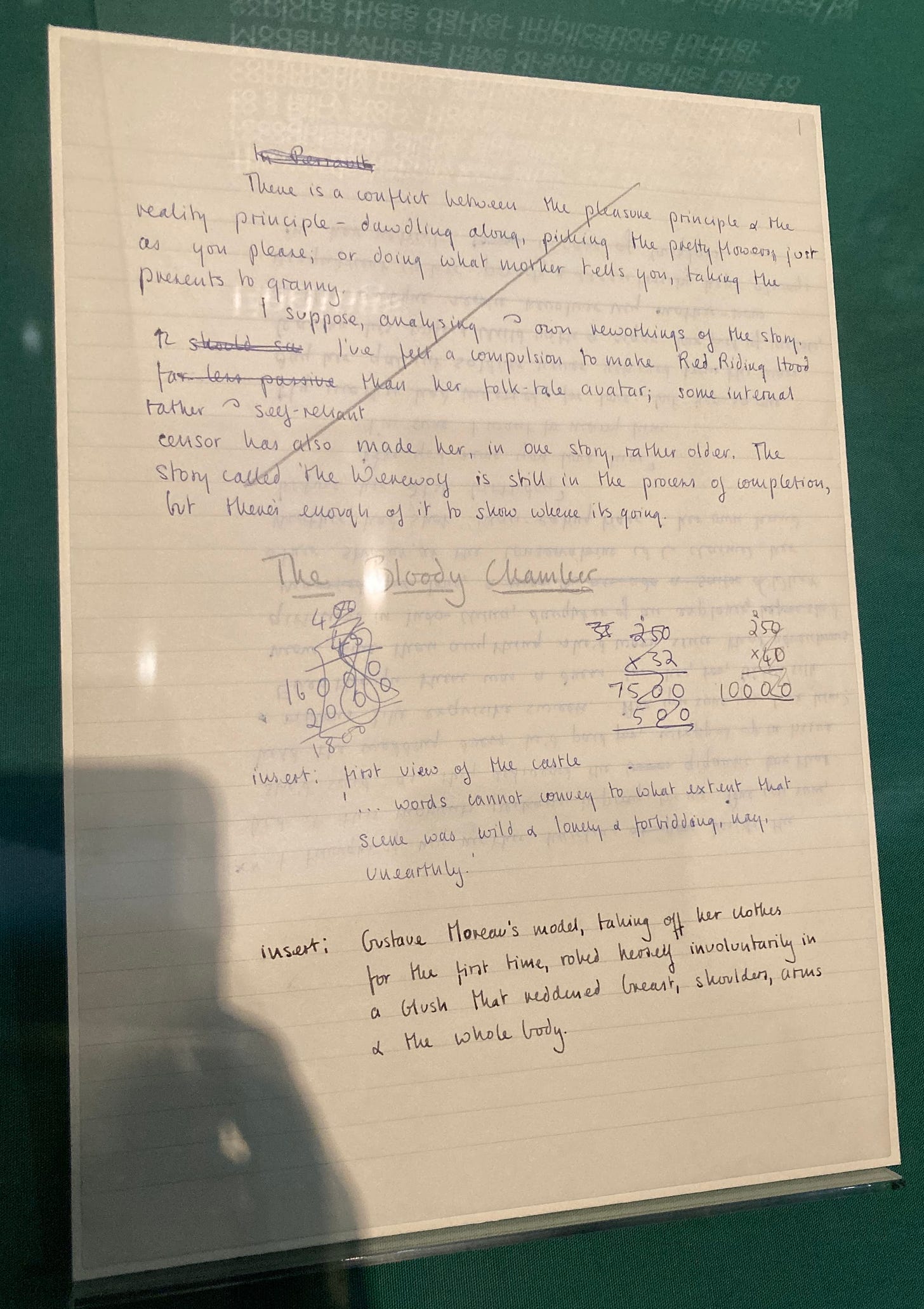

Angela Carter on Red Riding Hood (‘there is a conflict between the pleasure principle & the reality principle - dawdling along, picking the pretty flowers just as you please, or doing what mother tells you, taking the presents to granny’):

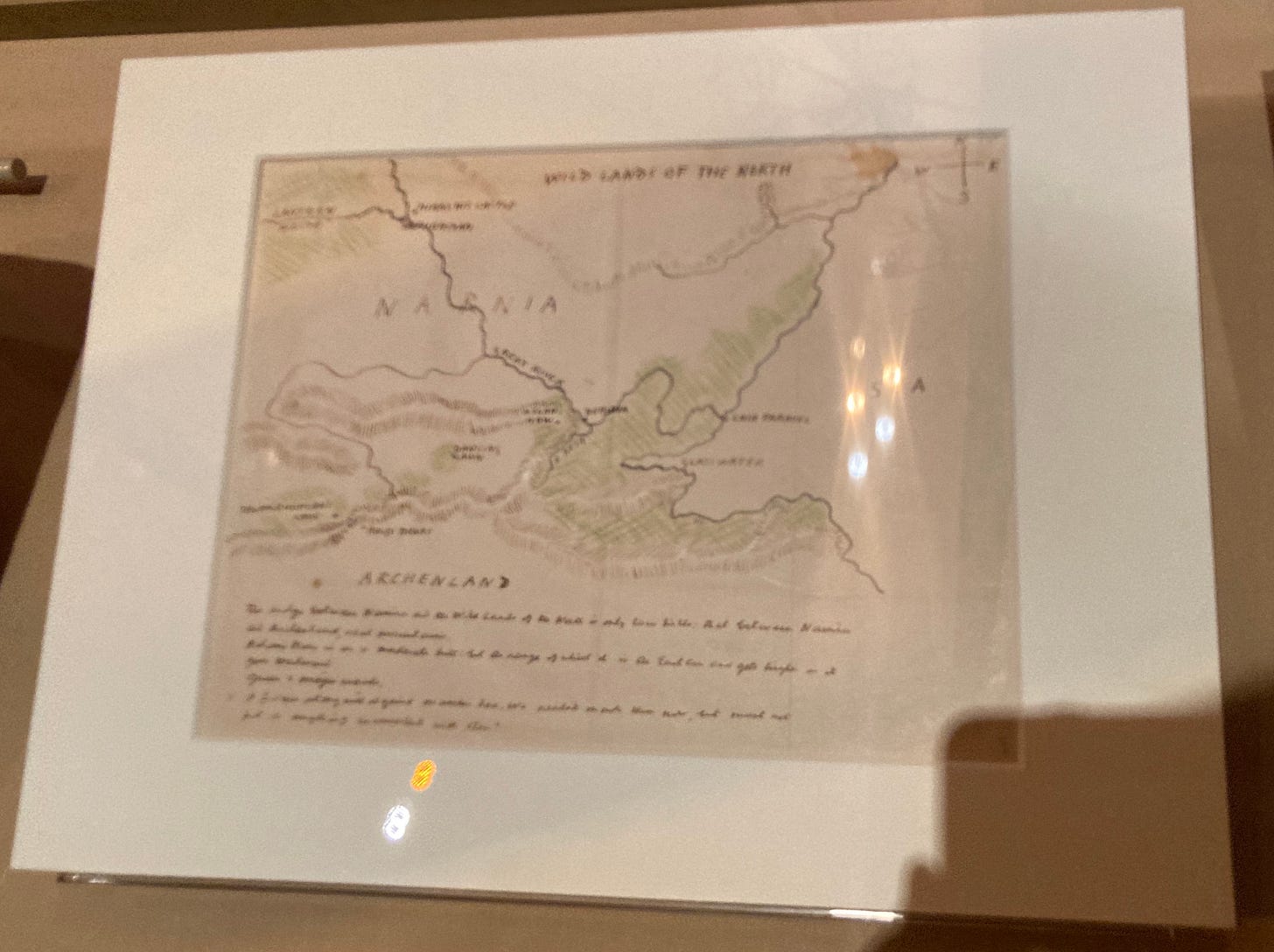

CS Lewis’ Narnia map:

Charlotte Brontë’s teenage stories in absolutely tiny handwriting:

And many more! Go! It ends Sunday 25 February.

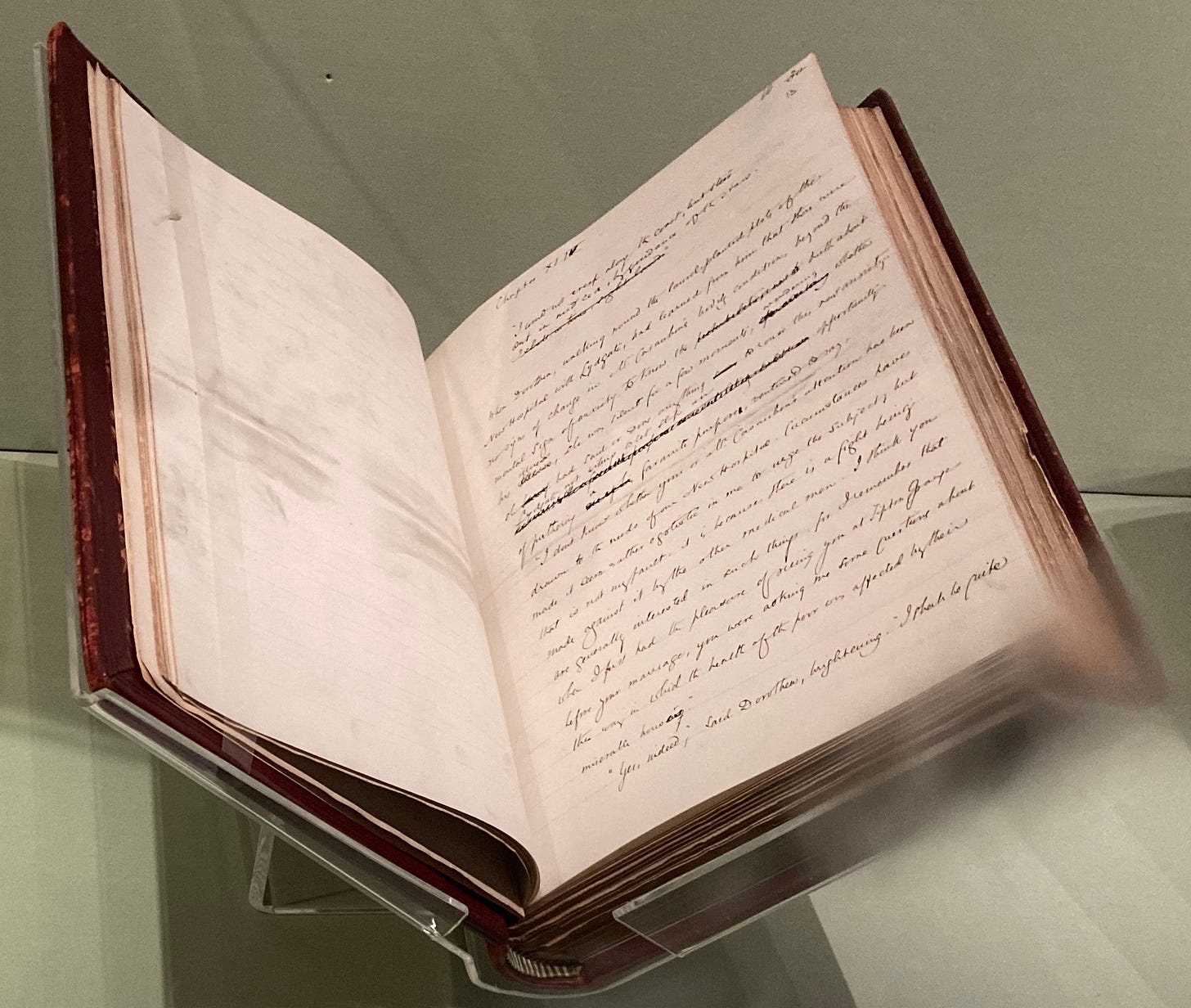

I also had a look at the BL’s permanent collection, which includes the manuscript of Middlemarch:

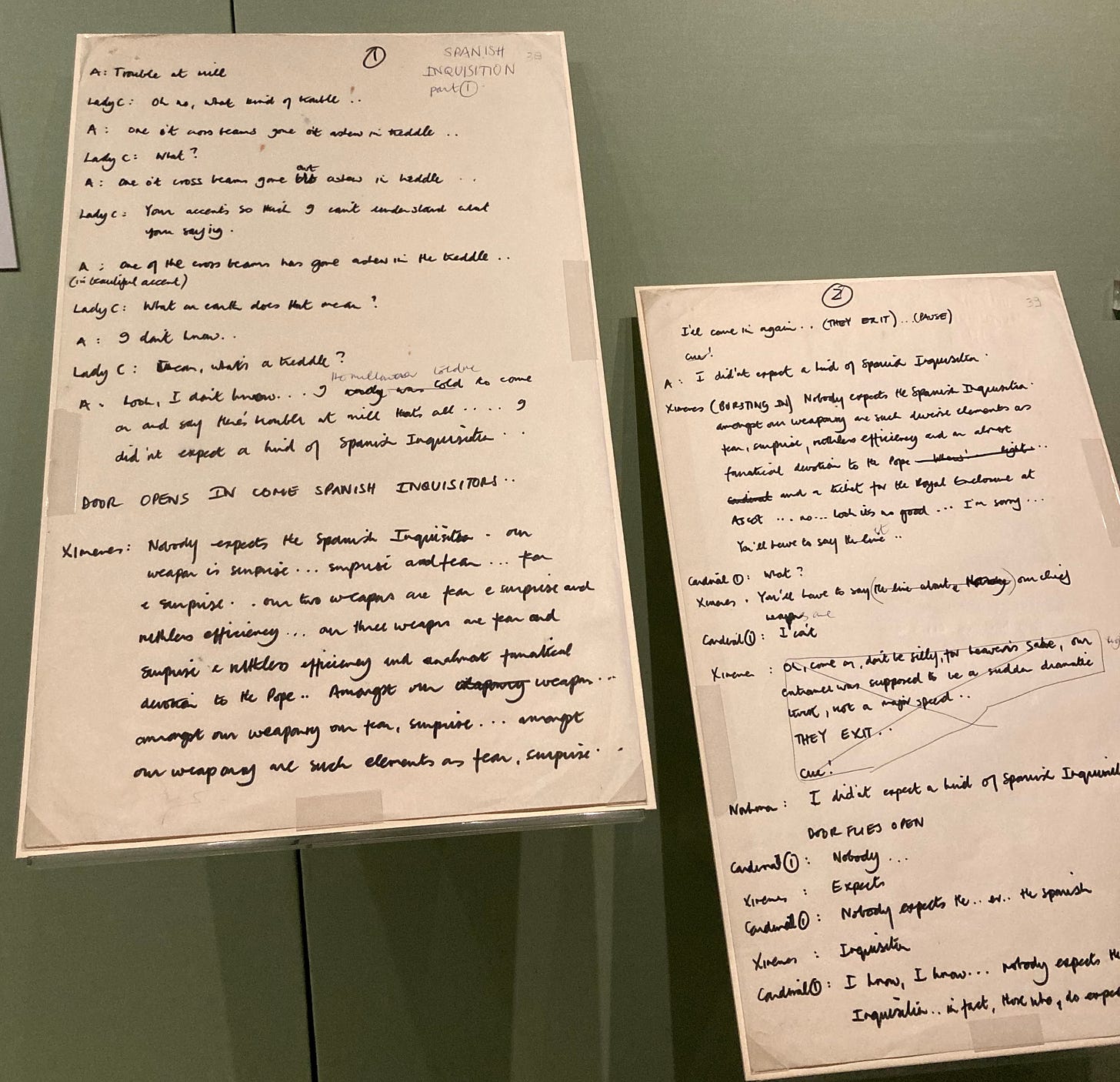

And pages of Monty Python scripts with one of their immortal lines:

3. Novelist as a Vocation by Haruki Murakami

In this collection of eleven essays, Murakami describes how he came to write, how he writes, the ups and downs of his career, and his advice to younger writers. (Essay titles include: ‘When I Became a Novelist’, ‘Making Time Your Ally: On Writing a Novel’, ‘What Kind of Characters Should I Include?’)

Murakami’s voice is so distinct and his advice is great, although as he insists over and over (something I wish many advice-givers less talented than him would do), it’s just his advice, and may work only for him.

He spent his twenties running his own jazz bar and slowly finishing his degree. He certainly wasn’t writing. And then, at twenty-nine, he attended a baseball game, and an idea fell out of the sky:

The satisfying crack when bat met ball resounded through Jingu Stadium. Scattered applause rose around me. In that instant, and based on no grounds whatsoever, it suddenly struck me: I think I can write a novel.

I can still recall the exact sensation. It was as if something had come fluttering down from the sky and I had caught it cleanly in my hands. I had no idea why it had chanced to fall into my grasp. I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now.

Murakami is very good on the possibilities that attends the writer, if they look closely:

Things the world sees as trivial can acquire weight over time, while other things broadly considered to be weighty can, quite suddenly, reveal themselves to be only hollow shells.

…So if you lament that you lack the material you need to write, you are giving up way too easily. If you just shift your focus a little bit and slightly alter your way of thinking, you will discover a wealth of material lying about just waiting to be picked up and used…All you need to do, as I said before, is retain your healthy writerly ambition. That is the key.

He explains why he keeps fit:

If you want to come face-to-face with the chaos inside you, then be silent and descend, alone, to the depths of your consciousness. The chaos we need to face, the real chaos that’s worth coming face-to-face with, is found precisely there.

…And what you need to faithfully, sincerely verbalize this is a quiet ability to focus, a staying power that doesn’t get discouraged, and a consciousness that is, up to a point, firm and systematic. And what you need to consistently maintain these qualities is physical strength. This might be seen as a boring, literally prosaic conclusion, but that’s my fundamental way of thinking as a novelist. Whether I’m criticized, praised, have rotten tomatoes thrown at me, or beautiful flowers tossed my way, that’s the only way I know how to write – and to live.

And he asks himself a very useful question:

This is purely my opinion, but if you want to express yourself as freely as you can, it’s probably best not to start out by asking ‘What am I seeking?’ Rather, it’s better to ask ‘Who would I be if I weren’t seeking anything?’ and then try to visualize that aspect of yourself.

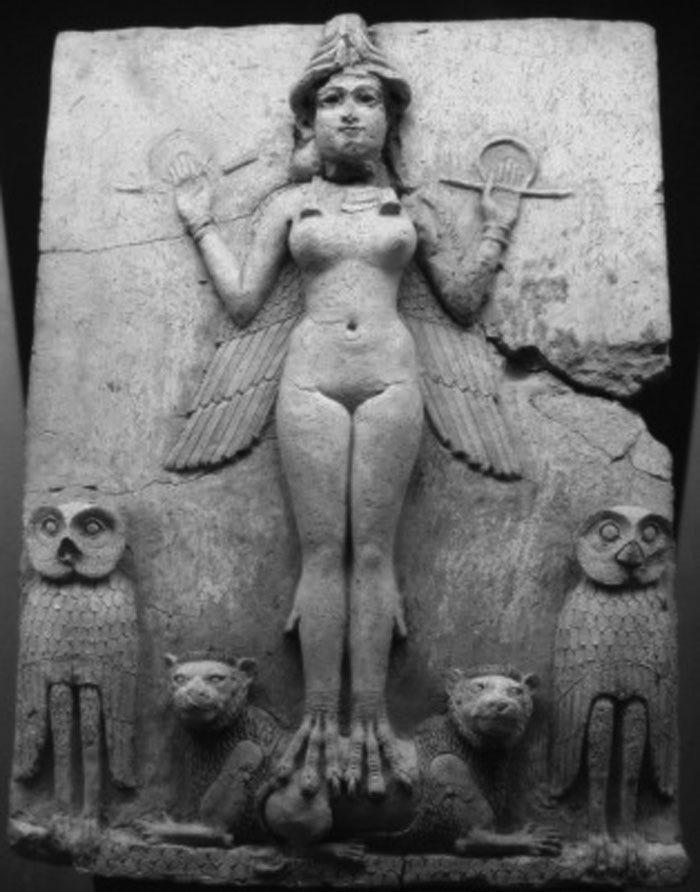

4. Did you know that the first known author is a woman?

No? I wonder why? I have just learnt of Endehuana, from a review in the LRB of Sophus Helle’s new translation of her poems.

Endehuana is the first named known author. She was born in 2286BC (1500 years before Homer, whoever he (or she or they) was (or were), and 1700 years before Sappho). She was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, a ruler who is attributed with creating the world’s first empire, after he conquered dozens of city states in southern Mesopotamia, binding them to the northern region he already controlled. The BBC have a good intro article on Endehuana here.

Endehuana’s father made her priestess of the moon god Nanna, to whom she was ritually married. She managed a temple and wrote poems and hymns; three of the former and 42 of the latter survive.

‘What would the history of Western literature look like if it began not with Homer and his war-hungry heroes but with a woman from ancient Iraq?’ Helle asks in his book, Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World’s First Author.

I have given birth,

Oh exalted lady, (to this song) for you.

That which I recited to you at (mid)night

May the singer repeat it to you at noon!

Enheduana, from The Exaltation of Inanna

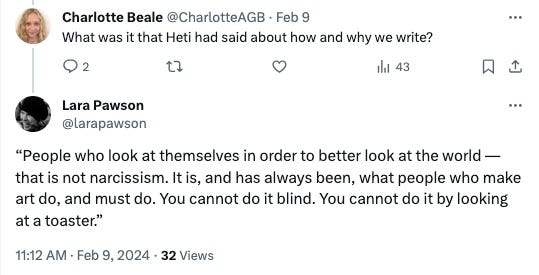

5. Lara Pawson on the power of writing against

Lara Pawson wrote Spent Light, which is being raved about everywhere. I’ve only read the first chapter, available on the publisher’s website here, but the synopsis reads:

A woman contemplates her hand-me-down toaster and suddenly the whole world erupts into her kitchen, in all its brutality and loveliness: global networks of resource extraction and forced labour, technologies of industrial murder, histories of genocide, alongside traditions of craft, the pleasures of convenience and dexterity, the giving and receiving of affection and care.

On Twitter/X last week, Pawson said that she had begun writing what became Spent Light in response to something Sheila Heti had said.

So I asked Pawson what exactly Heti had said to provoke her into writing. Pawson replied with a quote from Heti from this interview:

The power of writing against!

6. Michael Cunningham

I went to see Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours, speak about his new novel Day.

He spoke about how the idea for The Hours came about, which I found very interesting. The character Laura Brown (played by Julianne Moore in the film) was based on Cunningham’s mother, who, he said, as a housewife, lived a life ‘far too small’ for her. She would spend two hours shopping for cocktail napkins, return home, decide the napkins were wrong, then head back out again to buy different ones. Like Laura Brown, she threw a cake she had baked in the bin. It was when he compared his mother’s determination to banish her sorrow by baking the perfect cake with Virginia Woolf’s ambition to write, and Woolf’s own sorrow, that his plot was born. Cunningham was good on how it is still women, much more than men, who find themselves, in his words, ‘having agreed to a life that may be going not quite the way you thought it would’.

The Hours was his third novel. It was adapted into an Oscar-winning film, and made him a lot of money, very unexpectedly. He spoke about how his previous novel, A Home at the End of the World, had been savaged in the New York Times by the feared book critic Michiko Kakutani. He said he intends to go to her funeral and slip the novel into her casket.

7. Ian McEwan

I went to see Ian McEwan interviewed by Ella Berthoud at the London Library. He spoke about how he began to write, and it was funny and fascinating.

In his third year of undergraduate English at Sussex, he thought perhaps maybe he could write fiction. He found out about an English MA at UEA which offered one creative writing module, run by Malcolm Bradbury. So he rang up the university and asked for Bradbury. The person on the line replied, ‘speaking’. It turned out UEA was cancelling the course because no one had applied. McEwan said he was about to apply. So Bradbury told him to drive up next week with a few stories. McEwan didn’t have any stories to show – he just knew he wanted to write. So he spent five days knocking out what he could, which he duly showed Bradbury the following week. Bradbury accepted him. Tutorials consisted of twenty minutes in the pub, during which Bradbury barely commented on McEwan’s writing, apart from to ask for more.

8. Eminem’s mystic sentence trees

I loved this clip of a 2011 interview with Eminem, in which he talks about his boxes and boxes of notes. Thank you

for linking to a great blog by on it. Here’s Eminem:Even as a kid, I always wanted the most words to rhyme. Say I saw a word like ‘transcendalistic tendencies’. I would write it out on a piece of paper: ‘trans-cend-a-lis-tic ten-den-cies’ and underneath I’d line a word up with each syllable: ‘and bend all mystic sentence trees’. Even if it didn’t make sense, that’s the kind of drill I would do to practice.

9. Elif Batuman on writing outside recognised structures

is author of the excellent novels The Idiot and Either/Or, and also of one of the funniest books I’ve ever read, The Possessed, which is about the batshit world of Russian literature academia. (Her PhD (the pursuit of which furnished material for The Possessed, and chapters of which I once read online) was fascinating. It was about ‘double-entry bookkeeping’ in the novel - debit being time spent living to garner material, credit being time spent writing.)I loved this recent piece of hers on the risks and rewards of writing ‘outside most of the recognized structures of prestige and hierarchy’. Batuman ties in Ava DuVernay’s latest film Origin (about Isabel Wilkerson) with her own experience of moving from academia to the New Yorker to novels. Some excerpts below – but read it!

Basically, I experienced the trailer as a cinematic argument for – and celebration of – a kind of intellectual work that doesn’t fit in either the academy or in journalism, and that thus operates outside most of the recognized structures of prestige and hierarchy.

If you leave the hierarchical structure, you stop getting hierarchical compliments – and the privileged access (in this case, to the unreleased Trayvon Martin 911 tapes). It’s the thrill of being in the ‘current conversation’ – of doing something that ‘really matters’ (to important people, especially men).

Together, the European intellectual saying ‘your thesis is flawed’ and the US publisher saying, ‘I don’t see it’ represent the two fronts that a certain kind of writer has to defend against at all times. You have to prove both that you’re not ahistorical and unrigorous, and also that you aren’t an elitist talking over the heads of busy working Americans with attenuated attention spans.

It feels, too, like a feminist victory, because the people who do this kind of work – work driven by ideas and by feelings; work uniting personal experience and world events – are so often women. This is not, I think, because women are smarter than or different from men, but because they aren’t socialized as strongly to divorce emotional life from intellect, or to equate lack of hierarchical status with utter soul-death.

Ciao! Until next time!

I love this quote from Sheila Heti about the toaster! And I love Lara Pawson's challenge to it, and the fact that you asked her about it. I'm going to have to visit that British Library exhibit! Thanks for sharing this with us x