1. Meet Berta Ruck. You won’t regret it. It’s 1970, she’s 92, and she’s talking about being a young woman in Victorian Britain. (By this point, she’s a prolific romantic novelist, having published more than 90 books.) From 1:35:

2. I went to hear the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips talk about, among other things, giving up, which is the subject of his latest book. (Extracts from On Giving Up in The Guardian here and LRB here.

Some of the many interesting things he said:

The child with a depressed mother becomes compliant, because in meeting the mother’s needs, the child hopes that they might create the mother they need

Compliance destroys spontaneous creativity. Consideration also destroys spontaneous creativity. Spontaneous creativity is aliveness, and for Winnicott, aliveness is all

Giving up should be taught in schools as something children might do. If you grow up in a scenario that values persistence, ‘seeing things through’, finishing things rather than abandoning them, then you may become stuck with things, you are not free to revise

Giving up has to be justified (in today’s society) in a way that completion does not

Winnicott on how disease is easier to bear than health - aliveness is prolific, whereas disease narrows one’s mind. And narrowing attention, psychoanalysis believes, is not a good thing. (Fascism is a narrowing of attention, for example)

Brutality is a casualness or carelessness about loss

Psychoanalysis is a curiosity profession not a helping profession – it gets people to be interested in what they’re suffering from. (Don’t worry, Bion told one of his seminars, I’m not here to help you)

The analyst cares for someone rather than sets out to cure them, and then sees what they become in the analyst’s care

People should do an analysis to figure out what they want, then become an American pragmatist and go out and get it

Winnicott’s false self and true self: the true self may not necessarily be a helpful concept, as it can suck people into the tyranny of authenticity, but the false self is the compliant self, the part that forfeits what one wants to meet another’s wants instead

I like the Jonathan Lear quote in the first chapter of On Giving Up: ‘A courageous person has a proper orientation towards what is shameful and what is fearful.’

3. This brilliant Financial Times column by Simon Kuyper about writing being a collaborative act:

People have long understood that most acts of creation are collaborative: pop music, sport, films, inventing the atomic bomb. Only for books, especially fiction, does the presumption of the lone genius hang on. That might have surprised Shakespeare, who co-wrote some of his plays and adapted many from other writers’ work. But at some point, literature grew snooty about collaboration.

With reference to Orwell, Elena Ferrante, Lennon/McCartney and more.

(My dear MFA friends, we have a free subscription to the FT through the university library.)

4. The Nether World by George Gissing

I had not read Gissing before. He is brilliant! The Nether World is about the slums of Clerkenwell in the late Victorian period. The characters are perfect novelistic characters, in being both immediately and intimately known by the reader, as someone we have met in our own lives, but also entirely individual. Sidney Kirkwood, Clara Hewett and Jane Snowdon deserve to be better known. Michael Snowdon is a brilliant exemplar of the perversity of idealising poverty.

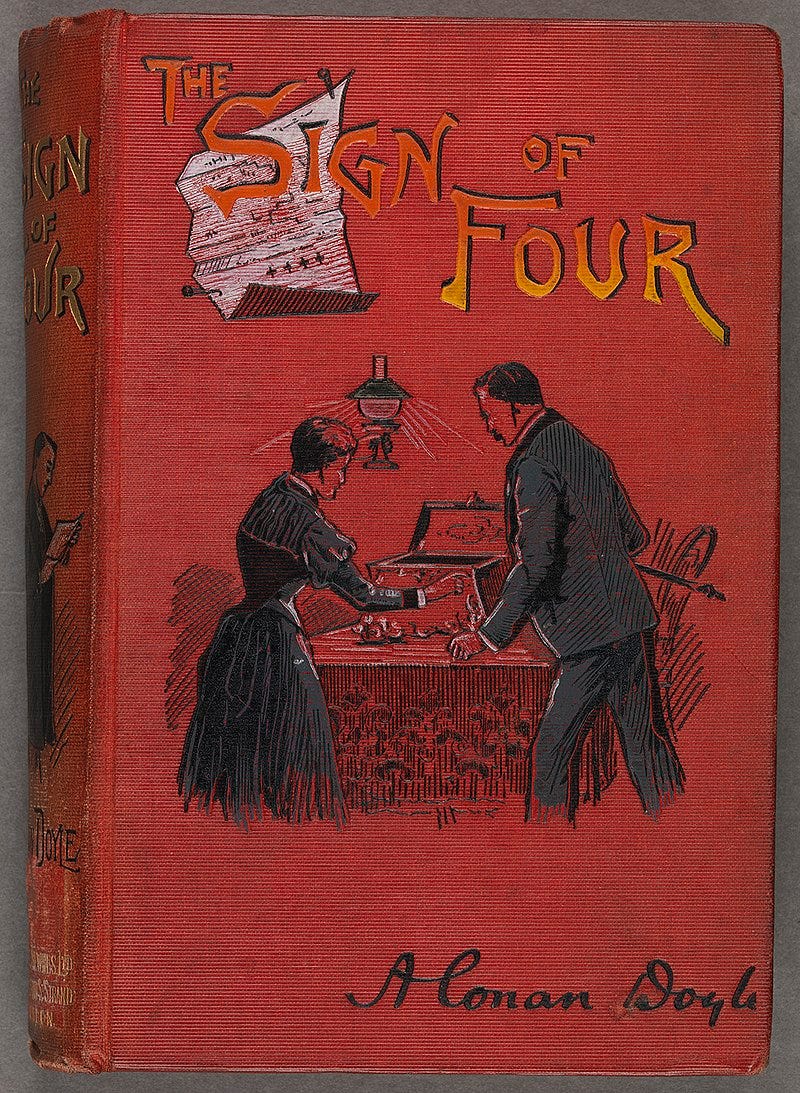

5. I also read my first Sherlock Holmes! It was so good. And so funny.

I enjoyed it a lot more than I expected to, as I have never really read detective fiction, apart from a clutch of Agatha Christie stories in my teens.

A snapshot of the Holmes/ Watson repartee - the opening of The Valley of Fear:

Holmes is the second-most adapted character in English literature, apparently, after Dracula.

6. This brilliant, short paper by Jasna Russo on psychiatrization, assertions of epistemic justice, and the question of agency:

The biomedical framing of human crises and the practice of psychiatric diagnosing are hardly ever considered as a foundation of othering, or as principal enablers of epistemic (and other) injustice.

(Epistemic justice is a concept from the philosopher Miranda Fricker to describe when somebody is wronged in their capacity as a knower. For how cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) perpetrates this, read the philosopher Sahanika Ratyanake’s work on it, well summarised in Psychology Today.)

Fricker further differentiates epistemic injustice into:

Testimonial injustice: ‘when prejudice causes a hearer to give a deflated level of credibility to a speaker's word’

And hermeneutical injustice: ‘when a gap in collective interpretive resources puts someone at an unfair disadvantage when it comes to making sense of their social experiences’

In the context of mental health services, Russo continues:

The division between a hard-to-comprehend them who need skilled and knowledgeable us to put forward their epistemic claims is enshrined in the work of various experts. The fundamental contradiction between the declared aims of such undertakings and their ethics and methodologies is rarely at issue, including for those whose marginalized ways of knowing are at stake.

Related to this, I am seeing more articles in mainstream publications raising awareness of the unintended consequences of psychiatric diagnosis. This in The Times yesterday, for example, about a recent paper co-authored by the director of UCL Institute of Mental Health on the rise of people self-diagnosing.

7. The Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran:

To suffer is the great modality of taking the world seriously.

Until next time.